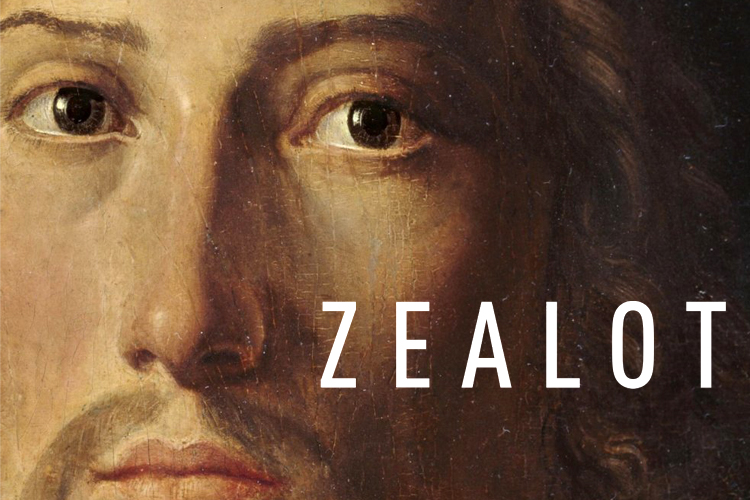

Your Own Personal Jesus: Reza Aslan's "Zealot"

/As a critic, I judge a work—whether it is a film, a play or book—on its merit to effectively fulfill the rigor of storytelling. Are the characters credible? Do we care about them? Is there tension? Is the pacing consistent? Are we immersed in the circumstances of the characters? Does the plotting serve the theme? Does the theme reveal and enlighten the reader about the universal nature of humanity? Using these criteria, Reza Aslan’s Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth is a success. Due to the controversial nature of writing a biography on Jesus, however, Aslan’s “biography” is primed for scrutiny.

When I spoke with Aslan at a dinner for the Los Angeles Review of Books (watch a video clip of Aslan's talk below), he told me I gave him the best compliment a writer could wish for. I was a quarter way into Zealot and sharing my experience thus far. I told Aslan how each time I opened the book, I marveled at the fact that I was reading about such legendary figures as John the Baptist or Pontius Pilate or, (my god!) Jesus Christ, and being placed so compellingly in their time period, I felt as if I were meeting people I could have never fathomed encountering.

As I continued reading, I realized what a neophyte I was when it came to the ancient world of the historical Jesus. Naturally, for me, and likely most of the reading population, entering the world of Jesus was akin to having any mythic figure come to life. Aslan’s talent as a writer notwithstanding, I would have had a similar reaction reading a biography on Santa Claus based on apocryphal stories suddenly unearthed about the jolly father of Christmas. Only, of course, if I were willing to suspend my disbelief, which is exactly what a satisfactory reading of Zealot requires. If you’re willing to accept assumptions Aslan makes, you’re in for a great read. You can then bask in the sumptuous world he creates out of first-century Palestine as you’re led through a narrative of the life of Jesus.

Reza Aslan photo by Malin Fezehai

The problem, of course, is that Aslan must use the gospels to both legitimize his argument and delegitimize logic that detracts from his argument. My response to that is go to the book’s Introduction. There Aslan quotes Rudolf Bultmann, known for saying, “the quest for the historical Jesus is ultimately an internal quest.” Aslan continues, “Scholars tend to see the Jesus they want to see. Too often they see themselves—their own reflection—in the image of Jesus they have constructed.”

Aslan seems to be confessing that his biography of Jesus is his own, internal quest. Critics can’t really dispute that. (An interesting fact: In C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia the Lion character, Aslan, represents Jesus.) My image of Jesus is of a Gandhi-like pacifist who taught that the “kingdom of heaven” is within, not in the clouds with some sky daddy. Imagine my surprise when I found myself chafing against Aslan’s proposition that Jesus was a zealot, a rebel “willing to resort to extreme acts of violence if necessary.”

In order to maintain my own personal Jesus, I began looking for flaws in Aslan’s argument. When I read that Pilate had sent “thousands and thousands of Jews to the cross,” which is based on historical fact, I could easily dismiss Aslan’s premise that Jesus’ crucifixion, which is not based on historical fact, meant he was a rebel zealot. In ancient Rome, insurrectionists were sentenced to crucifixion. If thousands had been sent to the cross, couldn’t Jesus have been just one more unjustly accused of treason? If Jesus was unjustly accused, Aslan’s entire premise of Jesus as a “Jewish nationalist who donned the mantle of the messiah and launched a foolhardy rebellion against the corrupt Temple priesthood and the vicious Roman occupation” falls apart. Clearly, I had to lay to rest my own preconceptions in order to enjoy the story. I couldn’t help but mark up the margins when I encountered an assumption, but this no longer detracted from the art of Aslan’s storytelling, which is more truthful in and of itself than mere “facts,” a way of seeing the ancients understood. Facts were not as important as Truth with a capital T.

Aslan ends the book underlining his personal “quest,” or reason for writing it: “The one thing any comprehensive study of the historical Jesus should hopefully reveal is that Jesus of Nazareth—Jesus the man—is every bit as compelling, charismatic, and praiseworthy as Jesus the Christ.” As the author of the forthcoming biography on Stella Adler, I hope I reveal that Stella, the legendary first lady of modern day acting, is every bit as compelling, charismatic, and praiseworthy as Stella the woman. En fin, when writing about larger-than-life figures, the biographer’s job boils down to separating the legend from the flesh-and-blood human being. Whatever your belief about Jesus—as the messiah, a peaceful preacher, a zealot, a myth—Aslan’s portrait evocatively narrates the life of a man who changed the course of history.